At Seabury, we focus on hands-on, experiential learning, and this unit is a prime example. We began the study of animal taxonomy and classification, not by diving right in to learn about Carolus Linnaeus and memorizing the different levels of classification (this comes later - stay tuned for a later post on this), but by thinking like scientists and trying to get at the big picture - why is it important for scientists to classify living things? How can that help us understand animals better? Why do we even care, or, through the lens of our overarching concept this year: What is it that we "treasure" about animals?

So, instead, we started learning about animals by looking at our shoes. Yes, our shoes. It all began with "The Great Shoe Sort" -- each of us put one shoe onto the paper-covered classroom floor, and then we went about sorting and classifying our shoes by paying attention to different characteristics. We noticed different groupings such as how they were fastened: shoes with laces and without laces, shoes fastened with velcro and slip-on shoes with no fasteners; and also what different shoes were designed for: athletic shoes vs. dressy shoes, etc.

We started dividing the shoes into groups by characteristics like these, and kept sorting until we had 19 different "species" of shoes, each with a unique set of characteristics.

Then we moved on to sorting and classifying stuffed animals. The students were asked to think like scientists and to sort the animals into categories that might be useful to scientists.

They came up with major categories like land animals vs. sea animals ...

Mammals vs. fish ...

Creatures with claws and creatures without claws...

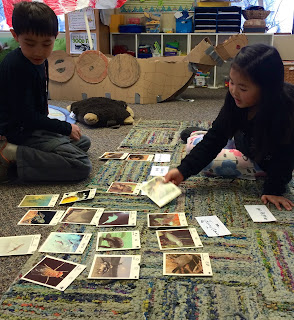

Then we did this activity one more time using animal identification cards. We chose cards on animals we were interested in, read the back of the card to learn about the different animal attributes, and then sorted the cards into groups, again trying to think about it from a scientist's perspective. This time, the groupings were focused onto even more specific attributes, including one group that looked at the skull shape as well as the type of teeth:

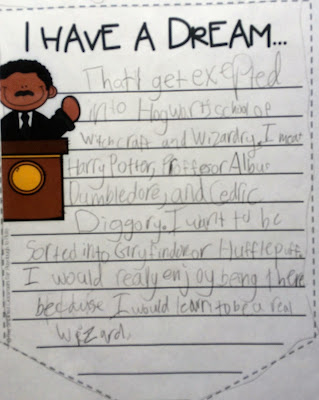

Finally, we wrote justifications for why we chose to classify the animals the way we did:

Using their critical thinking and inductive reasoning skills, and without yet being presented any information on how scientists do actually classify animals, the Gemstones came remarkable close to identifying the major classes of vertebrates (you can see above that students grouped animals into categories such as mammals, reptiles, fish and birds) and made some good insights into how these grouping help us understand animals better. Students noted in their writings, above, that knowing what they eat (herbivores/carnivores/omnivores) and where they live can help us understand where they originated, where they live now, and what their needs are. Not bad, for 7 and 8 year olds - budding young scientific minds at work!